The Thing (listening device)

The Thing, also known as the Great Seal bug, was one of the first covert listening devices (or "bugs") to use passive techniques to transmit an audio signal. It was concealed inside a gift given by the Soviets to the US Ambassador to Moscow on August 4, 1945. Because it was passive, being energized and activated by electromagnetic energy from an outside source, it is considered a predecessor of RFID technology.[1]

Creation

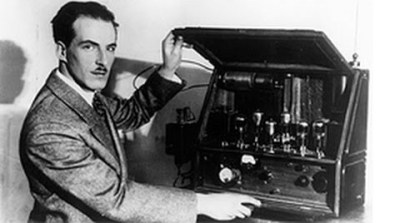

The Thing was designed by Soviet Russian inventor Léon Theremin,[2] whose best-known invention is the electronic musical instrument the theremin.

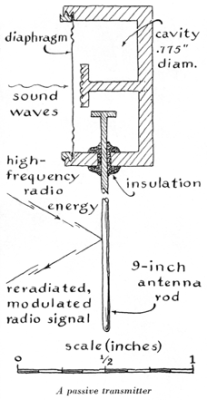

The principle used by The Thing, of a resonant cavity microphone, had been patented by Winfield R. Koch of the Radio Corporation of America (RCA) in 1941. In US patent 2,238,117 he describes the principle of a sound-modulated resonant cavity. High-frequency energy is inductively coupled to the cavity. The resonant frequency is varied by the change in capacitance resulting from the displacement of the acoustic diaphragm.[3]

Installation and use

The device was used by the Soviet Union to spy on the United States. It was embedded in a carved wooden plaque of the Great Seal of the United States. On August 4, 1945, a delegation from the Young Pioneer organization of the Soviet Union presented the bugged carving to U.S. Ambassador W. Averell Harriman, as a "gesture of friendship" to the USSR's World War II ally. It hung in the ambassador's Moscow residential study for seven years, until it was exposed in 1952 during the tenure of Ambassador George F. Kennan.[4]

Operating principles

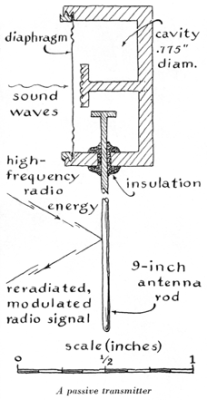

The Thing consisted of a tiny capacitive membrane connected to a small quarter-wavelength antenna; it had no power supply or active electronic components. The device, a passive cavity resonator, became active only when a radio signal of the correct frequency was sent to the device from an external transmitter. This is currently referred in NSA parlance as 'illuminating' a passive device. Sound waves caused the membrane to vibrate, which varied the capacitance "seen" by the antenna, which in turn modulated the radio waves that struck and were re-transmitted by the Thing. A receiver demodulated the signal so that sound picked up by the microphone could be heard, just as an ordinary radio receiver demodulates radio signals and outputs sound.

Theremin's design made the listening device very difficult to detect, because it was very small, had no power supply or active electronic components, and did not radiate any signal unless it was actively being irradiated remotely. These same design features, along with the overall simplicity of the device, made it very reliable and gave it a potentially unlimited operational life.

Technical details[edit]

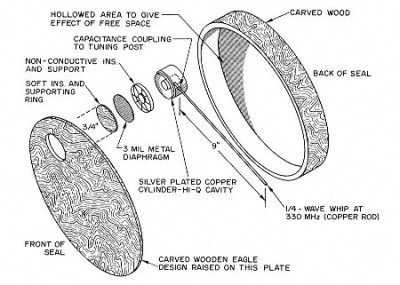

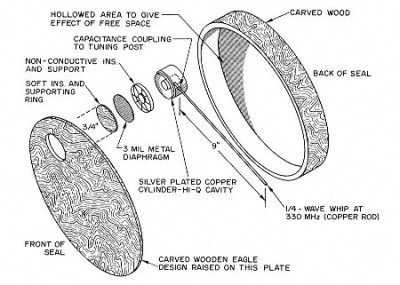

The device consisted of a 9-inch (23 cm) long monopole antenna (quarter-wave for 330 Megahertz(MHz) frequencies, but able to also act as half-wave or full-wave, the accounts differ)—a straight rod, led through an insulating bushing into a cavity, where it was terminated with a round disc that formed one plate of a capacitor. The cavity was a high-Q round silver-plated copper "can", with the internal diameter of 0.775 in (19.7 mm) and about 11/16 in (17.5 mm) long, with inductance of about 10 nanohenry.[5] Its front side was closed with a very thin (3 mil, or 75 micrometers) and fragile conductive membrane. In the middle of the cavity was a mushroom-shaped flat-faced tuning post, with its top adjustable to make it possible to set the membrane-post distance; the membrane and the post formed a variable capacitor acting as a condenser microphone and providing amplitude modulation (AM), with parasitic frequency modulation (FM) for the re-radiated signal. The post had machined grooves and radial lines into its face, probably to provide channels for air flow to reduce pneumatic damping of the membrane. The antenna was capacitively coupled to the post via its disc-shaped end. The total weight of the unit, including the antenna, was 1.1 ounce (31 grams).

The length of the antenna and the dimensions of the cavity were engineered in order to make the re-broadcast signal a higher harmonic of the illuminating frequency. (Note that the transmitting frequency is higher than the illuminating one.)[6]

The original device was located with the can under the beak of the eagle on the Great Seal presented to W. Averell Harriman (see below); accounts differ on whether holes were drilled into the beak to allow sound waves to reach the membrane. Other sources say the wood behind the beak was undrilled but thin enough to pass the sound, or that the hollowed space acted like a soundboard to concentrate the sound from the room onto the microphone.

The illuminating frequency used by the Soviets is said to be 330 MHz.[7]

Discovery

The existence of the bug was discovered accidentally by a British radio operator at the British embassy who overheard American conversations on an open radio channel as the Soviets were beaming radio waves at the ambassador's office. An American State Department employee was then able to reproduce the results using an untuned wideband receiver with a simple diode detector/demodulator,[8] similar to some field strength meters.

Two additional State Department employees, John W. Ford and Joseph Bezjian, were sent to Moscow in March 1951 to investigate this and other suspected bugs in the British and Canadian embassy buildings. They conducted a technical surveillance counter-measures "sweep" of the Ambassador's office, using a signal generator and a receiver in a setup that generates audio feedback ("howl") if the sound from the room is transmitted on a given frequency. During this sweep, Bezjian found the device in the Great Seal carving.[8]:2

The Central Intelligence Agency set about to analyze the device, and hired people from the British Marconi Company to help with the analysis. Marconi technicianPeter Wright, a British scientist and later MI5 counterintelligence officer, ran the investigation.[8] He was able to get The Thing working reliably with an illuminating frequency of 800 MHz. (The generator which had discovered the device was tuned to 1800 MHz.)

The membrane of the Thing was extremely thin, and was damaged during handling by the Americans; Wright had to replace it.

The simplicity of the device caused some initial confusion during its analysis; the antenna and resonator had several resonant frequencies in addition to its main one, and the modulation was partially both amplitude modulated and frequency modulated. The team also lost some time on an assumption that the distance between the membrane and the tuning post needed to be increased to increase resonance.

Aftermath

Wright's examination led to development of a similar British system codenamed SATYR, used throughout the 1950s by the British, Americans, Canadians and Australians.

There were later models of the device, some with more complex internal structure (the center post under the membrane attached to a helix, probably to increase Q), and some American models with dipole antennas. Maximizing the Q-factor was one of the engineering priorities, as this allowed higher selectivity to the illuminating signal frequency, and therefore higher operating distance and also higher acoustic sensitivity.[8]

In 1960, The Thing was mentioned on the fourth day of meetings in the United Nations Security Council, convened by the Soviet Union over the 1960 U-2 incidentwhere a U.S. spy plane had entered their territory and been shot down. The U.S. ambassador showed off the bugging device in the Great Seal to illustrate that spying incidents between the two nations were mutual and to allege that Nikita Khrushchev had magnified this particular incident out of all proportion as a pretext to abort the 1960 Paris Summit.[9]

The creation of Léon Theremin’s bug can be attributed to the success of his instrument. Theremin, the man, was a scientist by training. Theremin, the instrument, uses the player’s hand proximity to a pair of antennas to generate electronic sound. As a young student, Theremin was an aspiring physicist. World War One saw him enter military engineering school for radio operations. After the war, he worked on experiments as diverse as a device to measure the dielectric constant of gases and hypnosis. Léon even did work in Ivan Pavlov’s lab.

The creation of Léon Theremin’s bug can be attributed to the success of his instrument. Theremin, the man, was a scientist by training. Theremin, the instrument, uses the player’s hand proximity to a pair of antennas to generate electronic sound. As a young student, Theremin was an aspiring physicist. World War One saw him enter military engineering school for radio operations. After the war, he worked on experiments as diverse as a device to measure the dielectric constant of gases and hypnosis. Léon even did work in Ivan Pavlov’s lab.

The date was August 4, 1945. The european war was over, and the nuclear bombing of Hiroshima was only two days away. A group of 10 to 15 year old boys from the Young Pioneer Organization of the Soviet Union arrived at the US embassy carrying a hand carved great seal of the United States of America. They presented the seal to W. Averell Harriman, the US ambassador to the Soviet Union. The seal was given as a gesture of friendship between the US and Soviet Union. Harriman hung the plaque in the study of his residence, Spaso House. Unbeknownst to Harriman, the seal contained Theremin’s sophisticated listening device. The device, later known as “The Thing”, would not be discovered until 1952 — roughly seven years later.

The date was August 4, 1945. The european war was over, and the nuclear bombing of Hiroshima was only two days away. A group of 10 to 15 year old boys from the Young Pioneer Organization of the Soviet Union arrived at the US embassy carrying a hand carved great seal of the United States of America. They presented the seal to W. Averell Harriman, the US ambassador to the Soviet Union. The seal was given as a gesture of friendship between the US and Soviet Union. Harriman hung the plaque in the study of his residence, Spaso House. Unbeknownst to Harriman, the seal contained Theremin’s sophisticated listening device. The device, later known as “The Thing”, would not be discovered until 1952 — roughly seven years later.

The discovery of the great seal listening device is an interesting one. British broadcasters reported hearing American voices on the their radios in the vicinity of the American embassy. No Americans were transmitting though, which meant there had to be a bug. Numerous sweeps were performed, all of which turned up nothing. Joseph Bezjian had a hunch though. He stayed at the embassy pretending to be a house guest. His equipment was shipped in separately, disguised from Russian eyes. Powering up his equipment, Bezjian began a sweep of the building. With his receiver tuned to 1.6 GHz, he heard the bug’s audio, and quickly isolated the source in the great seal. Close inspection of the carving found it had been hollowed out, and a strange device placed behind the eagle’s beak. No batteries or wires were evident, and the device was not powered through the nail which had been hanging the seal. Bezjian removed the device from the great seal and was so cautious the he slept with it under his pillow that night for safe keeping. The next day he sent it back to Washington for analysis.

The discovery of the great seal listening device is an interesting one. British broadcasters reported hearing American voices on the their radios in the vicinity of the American embassy. No Americans were transmitting though, which meant there had to be a bug. Numerous sweeps were performed, all of which turned up nothing. Joseph Bezjian had a hunch though. He stayed at the embassy pretending to be a house guest. His equipment was shipped in separately, disguised from Russian eyes. Powering up his equipment, Bezjian began a sweep of the building. With his receiver tuned to 1.6 GHz, he heard the bug’s audio, and quickly isolated the source in the great seal. Close inspection of the carving found it had been hollowed out, and a strange device placed behind the eagle’s beak. No batteries or wires were evident, and the device was not powered through the nail which had been hanging the seal. Bezjian removed the device from the great seal and was so cautious the he slept with it under his pillow that night for safe keeping. The next day he sent it back to Washington for analysis.

The great seal bug quickly became known as “The Thing”. It was a passive resonant cavity device, containing no batteries or other power source. It consisted of an antenna and a small cylinder. One side of the cylinder was solid. The other side consisted of a very thin diaphragm, obviously some sort of microphone. Passive resonant cavities had been explored before, both in the US and abroad, but this is the first time we know of that was used for clandestine purposes. In his book Spycatcher, British operative Peter Wrightclaims that the US came to him for help determining how the device worked. However he is not mentioned in other accounts of Theremin’s bug.

The great seal bug quickly became known as “The Thing”. It was a passive resonant cavity device, containing no batteries or other power source. It consisted of an antenna and a small cylinder. One side of the cylinder was solid. The other side consisted of a very thin diaphragm, obviously some sort of microphone. Passive resonant cavities had been explored before, both in the US and abroad, but this is the first time we know of that was used for clandestine purposes. In his book Spycatcher, British operative Peter Wrightclaims that the US came to him for help determining how the device worked. However he is not mentioned in other accounts of Theremin’s bug.

Receive tuning (if it can be called such) was achieved by the precisely cut antenna. The RF carrier transmitted by the Russians would be received at the antenna and travel into the body of the device which was a resonant cavity. That resonant chamber was capacatively coupled to the thin conductive diaphragm which formed the microphone.

Receive tuning (if it can be called such) was achieved by the precisely cut antenna. The RF carrier transmitted by the Russians would be received at the antenna and travel into the body of the device which was a resonant cavity. That resonant chamber was capacatively coupled to the thin conductive diaphragm which formed the microphone.

The great seal bug disappeared for a number of years. The Russians knew we had caught them, and moved on to other espionage devices. It finally reappeared in 1960 at the United Nations. During the Gary Powers U2 incident, Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. presented the seal as concrete proof that Russia was spying on the Americans.

The great seal bug disappeared for a number of years. The Russians knew we had caught them, and moved on to other espionage devices. It finally reappeared in 1960 at the United Nations. During the Gary Powers U2 incident, Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. presented the seal as concrete proof that Russia was spying on the Americans.

Léon Theremin was released from his camp in 1947. He married Maria Guschina. This time the state did not intervene, and the pair had two children. In 1964, Theremin became a professor at the Moscow Conservatory. He lost his job after an article published in the New York times was read by the assistant director of the conservatory. The assistant director stated “Electricity is not good for music; electricity is to be used for electrocution” before throwing Theremin and his instruments out of the establishment. Through the 1970’s, Theremin worked in Moscow University’s Department of Acoustics. While there he built a polyphonic version of his instrument. Stored in a back room, the instrument was looted for parts by students and professors. Meanwhile, Theremin’s instrument was returning to vogue in the western world. Electronic music was hot, spawned by instruments such as the MiniMoog, and the Arp Kitten.

Léon Theremin was released from his camp in 1947. He married Maria Guschina. This time the state did not intervene, and the pair had two children. In 1964, Theremin became a professor at the Moscow Conservatory. He lost his job after an article published in the New York times was read by the assistant director of the conservatory. The assistant director stated “Electricity is not good for music; electricity is to be used for electrocution” before throwing Theremin and his instruments out of the establishment. Through the 1970’s, Theremin worked in Moscow University’s Department of Acoustics. While there he built a polyphonic version of his instrument. Stored in a back room, the instrument was looted for parts by students and professors. Meanwhile, Theremin’s instrument was returning to vogue in the western world. Electronic music was hot, spawned by instruments such as the MiniMoog, and the Arp Kitten.

THEREMIN’S BUG: HOW THE SOVIET UNION SPIED ON THE US EMBASSY FOR 7 YEARS

The man leaned over his creation, carefully assembling the tiny pieces. This was the hardest part, placing a thin silver plated diaphragm over the internal chamber. The diaphragm had to be strong enough to support itself, yet flexible enough to be affected by the slightest sound. One false move, and the device would be ruined. To fail meant a return to the road work detail, quite possibly a death sentence. Finally, the job was done. The man leaned back to admire his work.

The man in this semi-fictional vignette was Lev Sergeyevich Termen, better known in the western world as Léon Theremin. You know Theremin for the musical instrument which bears his name. In the spy business though, he is known as the creator of one of the most successful clandestine listening devices ever used against the American government.

The creation of Léon Theremin’s bug can be attributed to the success of his instrument. Theremin, the man, was a scientist by training. Theremin, the instrument, uses the player’s hand proximity to a pair of antennas to generate electronic sound. As a young student, Theremin was an aspiring physicist. World War One saw him enter military engineering school for radio operations. After the war, he worked on experiments as diverse as a device to measure the dielectric constant of gases and hypnosis. Léon even did work in Ivan Pavlov’s lab.

The creation of Léon Theremin’s bug can be attributed to the success of his instrument. Theremin, the man, was a scientist by training. Theremin, the instrument, uses the player’s hand proximity to a pair of antennas to generate electronic sound. As a young student, Theremin was an aspiring physicist. World War One saw him enter military engineering school for radio operations. After the war, he worked on experiments as diverse as a device to measure the dielectric constant of gases and hypnosis. Léon even did work in Ivan Pavlov’s lab.

In 1920, while working on his dielectric measurement device, Theremin noticed that an audio oscillator changed frequency when he moved his hand near the circuit. The Theremin was born. In November of 1920 Léon gave his first public concert with the instrument. He began touring with it in the late 1920’s and in 1928, he brought the Theremin to the United States. He set up a lab in New York and worked with RCA to produce the instrument.

Theremin’s personal life during this period was less successful than his professional endeavors. His wife, Katia, had come to America with him and studied medicine at a school about 35 miles from the City. For much of this time, Léon and Katia lived apart, seeing each other only a couple of times a week. While at school, Katia became associated with a fascist organization. The Russian Consulate caught wind of this and summarily divorced Léon from Katia. They couldn’t risk their rising star being associated with the Nazis.

Theremin eventually remarried, this time to Lavinia Williams, a ballerina. Lavinia was African-American and the couple faced ridicule in American social circles due to their mixed race. However, the Soviet Consulate did not have a problem with their relationship. In 1938, with the Nazi threat growing stronger, Theremin returned to Russia. He expected to send for his wife a few weeks after his arrival. Unfortunately, that wasn’t to be the case. Léon and Lavinia never saw each other again.

Upon arrival in Leningrad, Theremin was imprisoned, suspected of crimes against the state. He found himself working in a laboratory for the state department. This was not an unusual situation. Aircraft designer Andrei Tupolev and missile designer Sergei Korolyov were two of many others who faced a similar fate.

It was during this time as a prisoner that Theremin designed his listening device.

It was during this time as a prisoner that Theremin designed his listening device.

Placing the bug

The date was August 4, 1945. The european war was over, and the nuclear bombing of Hiroshima was only two days away. A group of 10 to 15 year old boys from the Young Pioneer Organization of the Soviet Union arrived at the US embassy carrying a hand carved great seal of the United States of America. They presented the seal to W. Averell Harriman, the US ambassador to the Soviet Union. The seal was given as a gesture of friendship between the US and Soviet Union. Harriman hung the plaque in the study of his residence, Spaso House. Unbeknownst to Harriman, the seal contained Theremin’s sophisticated listening device. The device, later known as “The Thing”, would not be discovered until 1952 — roughly seven years later.

The date was August 4, 1945. The european war was over, and the nuclear bombing of Hiroshima was only two days away. A group of 10 to 15 year old boys from the Young Pioneer Organization of the Soviet Union arrived at the US embassy carrying a hand carved great seal of the United States of America. They presented the seal to W. Averell Harriman, the US ambassador to the Soviet Union. The seal was given as a gesture of friendship between the US and Soviet Union. Harriman hung the plaque in the study of his residence, Spaso House. Unbeknownst to Harriman, the seal contained Theremin’s sophisticated listening device. The device, later known as “The Thing”, would not be discovered until 1952 — roughly seven years later.Discovered!

The discovery of the great seal listening device is an interesting one. British broadcasters reported hearing American voices on the their radios in the vicinity of the American embassy. No Americans were transmitting though, which meant there had to be a bug. Numerous sweeps were performed, all of which turned up nothing. Joseph Bezjian had a hunch though. He stayed at the embassy pretending to be a house guest. His equipment was shipped in separately, disguised from Russian eyes. Powering up his equipment, Bezjian began a sweep of the building. With his receiver tuned to 1.6 GHz, he heard the bug’s audio, and quickly isolated the source in the great seal. Close inspection of the carving found it had been hollowed out, and a strange device placed behind the eagle’s beak. No batteries or wires were evident, and the device was not powered through the nail which had been hanging the seal. Bezjian removed the device from the great seal and was so cautious the he slept with it under his pillow that night for safe keeping. The next day he sent it back to Washington for analysis.

The discovery of the great seal listening device is an interesting one. British broadcasters reported hearing American voices on the their radios in the vicinity of the American embassy. No Americans were transmitting though, which meant there had to be a bug. Numerous sweeps were performed, all of which turned up nothing. Joseph Bezjian had a hunch though. He stayed at the embassy pretending to be a house guest. His equipment was shipped in separately, disguised from Russian eyes. Powering up his equipment, Bezjian began a sweep of the building. With his receiver tuned to 1.6 GHz, he heard the bug’s audio, and quickly isolated the source in the great seal. Close inspection of the carving found it had been hollowed out, and a strange device placed behind the eagle’s beak. No batteries or wires were evident, and the device was not powered through the nail which had been hanging the seal. Bezjian removed the device from the great seal and was so cautious the he slept with it under his pillow that night for safe keeping. The next day he sent it back to Washington for analysis.Theory of Operation

The great seal bug quickly became known as “The Thing”. It was a passive resonant cavity device, containing no batteries or other power source. It consisted of an antenna and a small cylinder. One side of the cylinder was solid. The other side consisted of a very thin diaphragm, obviously some sort of microphone. Passive resonant cavities had been explored before, both in the US and abroad, but this is the first time we know of that was used for clandestine purposes. In his book Spycatcher, British operative Peter Wrightclaims that the US came to him for help determining how the device worked. However he is not mentioned in other accounts of Theremin’s bug.

The great seal bug quickly became known as “The Thing”. It was a passive resonant cavity device, containing no batteries or other power source. It consisted of an antenna and a small cylinder. One side of the cylinder was solid. The other side consisted of a very thin diaphragm, obviously some sort of microphone. Passive resonant cavities had been explored before, both in the US and abroad, but this is the first time we know of that was used for clandestine purposes. In his book Spycatcher, British operative Peter Wrightclaims that the US came to him for help determining how the device worked. However he is not mentioned in other accounts of Theremin’s bug.

Regardless of who figured out the device, the method of operation is devilishly simple. The Soviets would sit outside the embassy, either in another building or in a van. From this remote location they would aim a radio transmitter at the great seal. The bug inside would receive this signal and transmit voices in the room on a second, higher frequency. It did all of this with no standard internal components. No resistors, no tubes, no traditional capacitors, or the like. There were capacitive properties to the mechanism. For instance, a capacitor is formed between the diaphragm and the tuning peg of the device.

Receive tuning (if it can be called such) was achieved by the precisely cut antenna. The RF carrier transmitted by the Russians would be received at the antenna and travel into the body of the device which was a resonant cavity. That resonant chamber was capacatively coupled to the thin conductive diaphragm which formed the microphone.

Receive tuning (if it can be called such) was achieved by the precisely cut antenna. The RF carrier transmitted by the Russians would be received at the antenna and travel into the body of the device which was a resonant cavity. That resonant chamber was capacatively coupled to the thin conductive diaphragm which formed the microphone.

Sound waves would cause the diaphragm to move, which would vary the capacitance between the body and diaphragm, forming a condenser microphone. It is important to note that the bug didn’t transmit and receive on the same frequency. According to Peter Wright, the excitation frequency used by the Russians was actually 800 MHz. The cavity would resonate at a multiple of this base frequency, producing the 1.6 GHz output seen by Bezjian.

While bugs of this type have fallen out of favor, the idea of “illuminating” a device with an external transmitter lives on. Check out [Elliot’s] description of the RageMaster bug from the ANT catalog here. Resonant cavities have found common use as well. Every microwave oven or radar system with a magnetron uses one.

A Political Pawn

The great seal bug disappeared for a number of years. The Russians knew we had caught them, and moved on to other espionage devices. It finally reappeared in 1960 at the United Nations. During the Gary Powers U2 incident, Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. presented the seal as concrete proof that Russia was spying on the Americans.

The great seal bug disappeared for a number of years. The Russians knew we had caught them, and moved on to other espionage devices. It finally reappeared in 1960 at the United Nations. During the Gary Powers U2 incident, Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. presented the seal as concrete proof that Russia was spying on the Americans.

A replica of the great seal is on display at the NSA National Cryptologic Museum.

Afterward

Léon Theremin was released from his camp in 1947. He married Maria Guschina. This time the state did not intervene, and the pair had two children. In 1964, Theremin became a professor at the Moscow Conservatory. He lost his job after an article published in the New York times was read by the assistant director of the conservatory. The assistant director stated “Electricity is not good for music; electricity is to be used for electrocution” before throwing Theremin and his instruments out of the establishment. Through the 1970’s, Theremin worked in Moscow University’s Department of Acoustics. While there he built a polyphonic version of his instrument. Stored in a back room, the instrument was looted for parts by students and professors. Meanwhile, Theremin’s instrument was returning to vogue in the western world. Electronic music was hot, spawned by instruments such as the MiniMoog, and the Arp Kitten.

Léon Theremin was released from his camp in 1947. He married Maria Guschina. This time the state did not intervene, and the pair had two children. In 1964, Theremin became a professor at the Moscow Conservatory. He lost his job after an article published in the New York times was read by the assistant director of the conservatory. The assistant director stated “Electricity is not good for music; electricity is to be used for electrocution” before throwing Theremin and his instruments out of the establishment. Through the 1970’s, Theremin worked in Moscow University’s Department of Acoustics. While there he built a polyphonic version of his instrument. Stored in a back room, the instrument was looted for parts by students and professors. Meanwhile, Theremin’s instrument was returning to vogue in the western world. Electronic music was hot, spawned by instruments such as the MiniMoog, and the Arp Kitten.

Theremin finally visited the United States in 1992, reuniting with old friends. He performed in a concert at Stanfordand was interviewed by Robert Moog, who considered him to be a hero of the electronic music world. After filling in many of the blanks of his story, Theremin asked Moog and co-interviewer Olivia Mattis to be responsible when writing up their story. “But if you write that I have said something; against the Soviet government and that I have said that it is better to work elsewhere, then I shall have difficulties back home [ironic laughter]”. Even then at the twilight of his life, with the fall of the Soviet Union underway, Theremin was still looking over his shoulder, worried about what the government might do if he offended them.

Theremin passed away in 1993. The unlikely master of this spy-gadget was 97 years old.The Bugged Embassy Case: What Went Wrong

By ELAINE SCIOLINO, Special to the New York Times

Published: November 15, 1988

WASHINGTON, Nov. 14— In 1969, after years of tortuous negotiation, the Nixon Administration signed an agreement with the Soviet Union providing for new embassy complexes in Washington and Moscow.

The American project was to be the most elaborate and expensive United States embassy ever, a testament to American wealth and power.

Today, the eight-story American chancery in Moscow stands useless, infested with spying systems planted by Soviet construction workers, a stark monument to one of the most embarrassing failures of American diplomacy and intelligence in decades.

Over the years, the United States has spent $23 million on the building, but more than twice that amount in an attempt to figure out how the Soviets used eavesdropping devices to transform it into a giant antenna capable of transmitting written and verbal communications to the outside.

After a saga of suspicious behavior by Soviet work crews, electronic devices buried in concrete and investigators hanging like rock-climbers from the roof, a secret cable to the American Ambassador resulted, finally, in a halt to what a 1987 Senate committee described as ''the most massive, sophisticated and skillfully executed bugging operation in history.''

The Bush Administration will have to decide whether to follow President Reagan's advice that the building be torn down.

What went wrong is a spy story full of confusion, compromise and bureaucratic conflict. A Tale of Two Hills, And the Better Deal

The embassy saga dates back to 1934, when William C. Bullitt, the first American Ambassador to the Soviet Union, asked Stalin for a new embassy. But negotiations did not begin in earnest until the early 1960's.

Although the United States was offered a site high atop the Lenin Hills overlooking Moscow, it opted for an 85-year-lease on a site more accessible and centrally located: a 10-acre parcel overlooking the Moscow River and within walking distance of both the Ambassador's residence and important Soviet Government buildings.

Although neither side could have guessed it in 1969, when the site agreement was signed and eavesdropping techniques were less dependent on microwave telephone transmissions, the Soviets got the better deal, an elevated site on Mt. Alto, a hill overlooking Washington, tailor-made for espionage.

For four years, American and Soviet negotiators labored unsuccessfully over the terms of the construction. But in 1972, during the heady days of detente, President Nixon ordered a reluctant State Department to reach an agreement. In what would later be recognized as a crucial blunder, the United States gave the Soviets control of the design and construction of the mission in Moscow.

''I didn't favor it because it was a one-sided deal,'' recalled William P. Rogers, who signed off on the deal as Secretary of State in the Nixon White House. ''But I was carrying out the orders of the White House.''

But Dr. Henry A. Kissinger, Mr. Nixon's national security adviser at the time, declines to accept blame, saying the State Department did not voice strong objections. ''I don't exclude I said to somebody, 'See what you can do to get it done,' '' he said. ''But that isn't the same thing as saying, 'Go ahead, cost what it may.' ''

The Soviets proceeded to build pre-cast concrete pieces for the embassy building in their own factories, out of view of American security experts. In signing the accord, Washington miscalculated that inspection of the pieces as they arrived at the site would be sufficient to enable security personnel to detect eavesdropping devices. Since the United States had the right to do all the finishing work - from inside walls to windows and doors - there was little concern that the Soviets would be able to implant bugs that could not be detected. Security Slips Between the Cracks

From the outset, the project was beset by clashes within the Washington bureaucracy which delayed decisions on security matters. The chain of command was never clearly defined, as security, construction, diplomatic and intelligence functions were carried out by different offices with different agendas.

At the time of the groundbreaking in 1979, there was still no clear American plan for the on-site security needs or what the specialists were supposed to look for. American intelligence officials in Moscow warned that they would not have the necessary equipment and personnel to handle the problem of Soviet bugging once construction began.

By late 1979, several thousand precast elements of at least 7,000 pounds each were arriving on the building site. All of them had to be inspected. ''We started getting technical security people saying, 'Hey, guys, you have problems,' '' said a State Department official who was in Moscow at the time. ''They weren't listened to.''

Meanwhile, the State Department's Office of Foreign Buildings Operations, already under pressure from Congress because of cost overruns and poor results in construction projects in other capitals, was pushing to move the job along.

Instead, they found that the Soviet idea of efficient construction was vastly inferior to American standards, and they quickly lost patience with Russian absenteeism, drunkenness on the job and sloppy work habits.

''We treated this as a cost-driven operation and it became critical to move as quickly as possible,'' said Joseph S. Hulings 3d, the State Department's current coordinator on the embassy project.

Not until early 1982 was a specially trained team of security experts dispatched to Moscow. Armed with experimental X-ray scanning machines that could inspect construction elements without destroying them and cold-weather gear from Eddie Bauer, they invented inspection procedures as they went along.

The specialists were trained rock-climbers who worked through Moscow's winter nights in temperatures that fell to 40 degrees below zero, hanging off the side of the building to get from floor to floor.

The team was stunned when over the course of a few months, they discovered that the Soviets had put permanent eavesdropping systems into the actual structure of the building.

''We found things that didn't belong there based on shop drawings,'' said Frank Crosher, a security engineer who worked on the site from 1980 to 1982 and managed the embassy security team from Washington until 1986. ''We found cables in the concrete as well as design discrepancies, millions of bits of data.''

Along the way, they discovered interconnecting systems so sophisticated that they could not be removed from the steel and concrete columns, the beams, the pre-cast floor slabs and sheer walls between the columns. They found electronic ''packages'' where a piece of steel reinforcement in the flooring should have been, and resonating devices that allowed the Russians to monitor precisely both electronic and verbal communications.

Their job was made more difficult by decoys made to look like bugs and garbage from the construction process.

The Soviets, for their part, made every effort to thwart security efforts. In the spring of 1983, for example, after the American security team brought in new radiographic equipment to inspect structural columns, the Soviet construction workers went on a two-week strike, citing hazards to their health.

As work on the outer structure drew to a close, the Soviets suddenly became anxious to speed up construction of the top floors, where secret embassy functions were to be conducted. At the same time, an external Soviet-owned freight elevator was mysteriously disabled, which meant that Soviet workmen needed more access to the inside of the building.

But never did the American experts lose confidence that they could eventually figure out and neutralize the Soviet systems.

''Intelligence agents were saying, 'Give us a year and we'll fix it,' '' said one Administration official involved in the project. ''We had no other choice than to believe them. No one wanted to admit failure.''

Despite the mounting evidence of Soviet penetration, it took until August 1985 before the State Department ejected the Soviets from the construction site.

On Aug. 15, Mr. Lamb sent a secret cable to Ambassador Arthur A. Hartman recommending that he shut down the job. Mr. Hartman locked out the Soviets and stopped construction two days later. C.I.A.'s Confidence Plays Poorly in Congress

In late 1985, some members of Congress began to suspect that the problems might be irreparable. Following a visit to Moscow by staff members of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence in December, the committee scheduled a series of closed briefings on the matter in the spring of 1986.

It was then that the C.I.A. admitted for the first time that the Soviets had successfully incorporated complex and impenetrable surveillance systems into the building structure.

But the C.I.A. and many technical experts still remained convinced that they could crack the Soviet systems.

A lengthy, highly classified memo from the C.I.A. to the Senate Intelligence Committee in December 1986 asserted that American intelligence analysts and engineers would be able to neutralize the building, even though they acknowledged that they were not yet able to figure out the Soviet systems.

But allegations surfaced in the spring of 1987 that Marine guards had dated Soviet women and allowed K.G.B. agents access to sensitive information. Disclosures of the electronic penetration of the new embassy followed in April 1987, and for the first time, it became publicly known that the Soviets had installed a wide variety of intelligence-gathering devices whose technology was not understood by the United States.

At about the same time, the Senate Intelligence Committee unanimously recommended razing the building.

Still, the recommendation to tear the building down was vigorously opposed by the State Department, all the way up to Secretary of State George P. Shultz. Recommendation: The Wrecking Ball

Expert studies followed.

The President's Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board recommended in July 1987 spending about $80 million to use existing technology and develop new methods to clear the new chancery of eavesdropping devices. A report by James R. Schlesinger, a former Director of Central Intelligence, recommended destroying the top floors of the chancery and constructing a six-story annex at a cost of at least $35 million.

Finally, a study commissioned by the State Department concluded that razing the building and constructing a new one in its place would cost less, be less physically dangerous and take less time than neutralizing the listening systems in the uncompleted building. Mr. Shultz recommended to Mr. Reagan that the building be destroyed.

In the absence of Congressional objections, the State Department will begin a $3 million architectural and design plan for a new chancery next week. The Bush Administration will have to decide whether to accept Mr. Reagan's recommendation to raze and reconstruct the building, a project that could cost half a billion dollars and take another decade, according to some State Department estimates. President Reagan has made it clear that the Soviets, meanwhile, will not be allowed to occupy their new Washington embassy building, which is ready for use, until the United States moves into its own new quarters in Moscow.

In retrospect, the experts say, the embassy fiasco is a reflection of the American way of conducting diplomacy - the arrogance of negotiators who regarded treaty-signing as loftier than security matters, the hubris of intelligence experts who firmly believed that they could neutralize any system the Soviets could develop, and the bureaucratic inertia of American policymakers who ignored danger signs along the way.

''The culprit,'' Mr. Schlesinger said, ''is American complacency, the tendency to assume that the Russians are technically inferior to us and that we can handle them.''

Robert E. Lamb, Assistant Secretary of State for Diplomatic Security, put it more bluntly. ''We knew the Russians were going to bug it, but we were confident we could deal with it,'' he said. ''Obviously, we were wrong.''

Photo of the new U.S. Embassy in Moscow (NYT/Paul Hosefros)

Comments