MALWARE CAN STEAL DATA FROM NON-NETWORKED COMPUTERS, VIA HEAT

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

"HOT OR NOT?" COMES TO COMPUTER SECURITY

By Dan Moren Posted March 24, 2015

Back in 1999, Neal Stephenson's novel Cryptonomicon introduced me to the idea of Van Eck phreaking—intercepting the weak electromagnetic radiation from a computer monitor to recreate what the person is seeing on the screen. Now security researchers have come up with an exploit that uses an even simpler form of radiation: heat.

BitWhisper, as researchers Mordechai Guri and Professor Yuval Elovici of Ben-Gurion University's Cyber Security Research Center have dubbed their program, targets air-gapped machines—computers that are not physically (or wirelessly) connected to the Internet. By using malware that can tap into computers' cooling systems and temperature sensors, the hack can send information back and forth between two adjacent machines.

For example, raising the temperature of one computer by a single degree over a specified time period would be detected by the adjacent computer as a binary bit of '1'; returning it to the baseline temperature would be interpreted as a '0.' String enough of those together and they can represent a computer command or raw data, such as a password.

Naturally, there are a host of caveats. In order to work, the two computers need to be just 15 inches apart (close enough to detect the changes in heat), one needs to be connected to the internet, and they both have to be infected with the malware. And given the time inherent in raising and lowering temperatures, sending data takes a long time--potentially hours.

This isn't the first attempt to target air-gapped computers. The Stuxnet worm largely thought to have been developed by the U.S. National Security Agency and Israel jumped from computer to computer via compromised USB drives. Researchers have also come up with ways to transmit information between hacked computers using their built-in speakers to generate high-frequency sounds that can be heard by microphones but not ears. And Guri himself previously came up with an exploit called AirHopper that could transmit information as FM signals to nearby compromised mobile phones, which would then send that data on to the outside world.

As tempted as you may be to look askance at your computer the next time its fans kick on, don't worry too much: it's probably just running hot as it processes your high-def stream of House of Cards. Probably.

Scientist-developed malware prototype covertly jumps air gaps using inaudible sound

Malware communicates at a distance of 65 feet using built-in mics and speakers.

by Dan Goodin - Dec 3, 2013

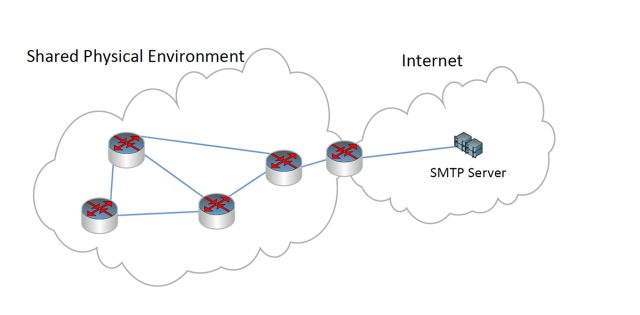

Enlarge / Topology of a covert mesh network that connects air-gapped computers to the Internet.

Computer scientists have proposed a malware prototype that uses inaudible audio signals to communicate, a capability that allows the malware to covertly transmit keystrokes and other sensitive data even when infected machines have no network connection.

The proof-of-concept software—or malicious trojans that adopt the same high-frequency communication methods—could prove especially adept in penetrating highly sensitive environments that routinely place an "air gap" between computers and the outside world. Using nothing more than the built-in microphones and speakers of standard computers, the researchers were able to transmit passwords and other small amounts of data from distances of almost 65 feet. The software can transfer data at much greater distances by employing an acoustical mesh network made up of attacker-controlled devices that repeat the audio signals.

The researchers, from Germany's Fraunhofer Institute for Communication, Information Processing, and Ergonomics, recently disclosed their findings in a paper published in the Journal of Communications. It came a few weeks after a security researcher said his computers were infected with a mysterious piece of malware that used high-frequency transmissions to jump air gaps. The new research neither confirms nor disproves Dragos Ruiu's claims of the so-called badBIOS infections, but it does show that high-frequency networking is easily within the grasp of today's malware.

"In our article, we describe how the complete concept of air gaps can be considered obsolete as commonly available laptops can communicate over their internal speakers and microphones and even form a covert acoustical mesh network," one of the authors, Michael Hanspach, wrote in an e-mail. "Over this covert network, information can travel over multiple hops of infected nodes, connecting completely isolated computing systems and networks (e.g. the internet) to each other. We also propose some countermeasures against participation in a covert network."

The researchers developed several ways to use inaudible sounds to transmit data between two Lenovo T400 laptops using only their built-in microphones and speakers. The most effective technique relied on software originally developed to acoustically transmit data under water. Created by the Research Department for Underwater Acoustics and Geophysics in Germany, the so-called adaptive communication system (ACS) modem was able to transmit data between laptops as much as 19.7 meters (64.6 feet) apart. By chaining additional devices that pick up the signal and repeat it to other nearby devices, the mesh network can overcome much greater distances.

The ACS modem provided better reliability than other techniques that were also able to use only the laptops' speakers and microphones to communicate. Still, it came with one significant drawback—a transmission rate of about 20 bits per second, a tiny fraction of standard network connections. The paltry bandwidth forecloses the ability of transmitting video or any other kinds of data with large file sizes. The researchers said attackers could overcome that shortcoming by equipping the trojan with functions that transmit only certain types of data, such as login credentials captured from a keylogger or a memory dumper.

"This small bandwidth might actually be enough to transfer critical information (such as keystrokes)," Hanspach wrote. "You don't even have to think about all keystrokes. If you have a keylogger that is able to recognize authentication materials, it may only occasionally forward these detected passwords over the network, leading to a very stealthy state of the network. And you could forward any small-sized information such as private encryption keys or maybe malicious commands to an infected piece of construction."

Remember Flame?

The hurdles of implementing covert acoustical networking are high enough that few malware developers are likely to add it to their offerings anytime soon. Still, the requirements are modest when measured against the capabilities of Stuxnet, Flame, and other state-sponsored malware discovered in the past 18 months. And that means that engineers in military organizations, nuclear power plants, and other truly high-security environments should no longer assume that computers isolated from an Ethernet or Wi-Fi connection are off limits.

The research paper suggests several countermeasures that potential targets can adopt. One approach is simply switching off audio input and output devices, although few hardware designs available today make this most obvious countermeasure easy. A second approach is to employ audio filtering that blocks high-frequency ranges used to covertly transmit data. Devices running Linux can do this by using the advanced Linux Sound Architecture in combination with the Linux Audio Developer's Simple Plugin API. Similar approaches are probably available for Windows and Mac OS X computers as well. The researchers also proposed the use of an audio intrusion detection guard, a device that would "forward audio input and output signals to their destination and simultaneously store them inside the guard's internal state, where they are subject to further analyses."

Update

On Wednesday Hanspach issued the following statement:

Fraunhofer FKIE is actively involved in information security research. Our mission is to strengthen security by the means of early detection and prevention of potential threats. The research on acoustical mesh networks in air was aimed at demonstrating the upcoming threat of covert communication technologies. Fraunhofer FKIE does not develop any malware or viruses and the presented proof-of-concept does not spread to other computing systems, but constitutes only a covert communication channel between hypothetical instantiations of a malware. The ultimate goal of the presented research project is to raise awareness for these kinds of attacks, and to deliver appropriate countermeasures to our customers.

Story updated to add "prototype" to the first sentence and headline and to change "developed" to "proposed," in the first sentence. The changes are intended to make clear the researchers have not created a piece of working malware.

PROMOTED COMMENTS

If it were using higher frequencies, they'd be able to transmit at a higher bandwidth. My bet is that they're using frequencies below the human hearing threshold, which would explain why the connection is so slow.

According to the paper they're in the near ultrasonic, so in the 20 kHz region. Even if they could go faster it is worth remembering that any environment is potentially very noisy. So for accurate transmission (and probably transmission that isn't obviously different from regular line noise to a sensitive human listener) they will need high redundancy in the link. They mention frequency hopping spread spectrum (which is already used for robust underwater transmission) and plenty of error correction.

In any case, we already train dogs to sniff for bombs and drugs. Clearly, training them to hear malware is just around the corner.

There are two complementary tasks that could be performed by separate pieces of software, although in practice one would probably want a single stealthy code that could both transmit and listen. One must cross the air-gap at least once to infect the high-value target. The listening computer (or at least one in the acoustic network) is presumed connected to a network, and relays the data in any of the usual ways.

I think the point is that crossing the air gap is a rare event (via e.g. infected USB keychain) compared to infecting even a fairly secured networked system, yet one wants data from the target as though it weren't. With an acoustic network you only need to cross the air gap once, and after that data can be relayed from the network-connected system much more regularly. Beats waiting for months until someone plugs the wrong USB keychain in again.

Being able to pass commands back to the target system through the acoustic network would be gravy, certainly, but once one-way communication has been established the marginal effort to do so is much smaller -- by that point both systems have already been infiltrated, so one might as well write that capability into the code in the first place unless that somehow significantly increases the odds of detection.

Of course not. The point of the research is that once infected by traditional means, computers connected to internet begin listening for sensitive information transmitted by audio signals from disconnected computers.

If you're breaking your laptop open to put a capacitor across your speaker why not cut the wires or put a mechanical switch in instead? The point is that 99.99% of people won't do that.

BitWhisper: The Heat is on the Air-Gap